Hannah L. Jacobs & Amanda Lazarus

In fall 2016, Wired! Lab core faculty Dr. Kristin Huffman Lanzoni decided to integrate digital archiving and visualization technologies into ARTHIST 256 Italian Baroque Art. She planned to engage students in these digital practices to enhance their exploration, analysis, and presentation of course content. With collaborators Hannah Jacobs, Wired! Lab Multimedia Analyst, and graduate Teaching Assistant Amanda Lazarus, she designed a project assignment that asked students to gather and organize primary source materials using the Omeka web content management system and to visualize their research through spatiotemporal narratives presented in the visualization plugin Neatline. Lanzoni and Jacobs had conducted similar courses in the past, with Jacobs providing technical instruction in Omeka and Neatline through in-class workshops, written tutorials, and consultations. With this course, however, Lazarus became a crucial addition to the instructional team as someone with knowledge of both the course’s historical content and the digital technologies.

Lazarus, a fourth year graduate student in Art, Art History & Visual Studies, studies Greek and Roman sculpture and is writing her dissertation on representations of female youths on classical Attic tombstones; their socioeconomical, political, and ideological significance; and what they convey about the status of women in antiquity. In 2013, Lazarus enrolled in the Wired! Lab’s New Representations in Technology, a seminar that examined digital humanities theories and methods with an emphasis on visualization. The class engaged in digital skill-building through hands-on workshops and critical discussions, the latter in collaboration with the National Humanities Center and other digital humanities courses at Triangle universities. It was in this course that Amanda was introduced to Omeka, a digital archiving content management system designed for scholars, librarians, and curators, and Neatline, a mapping and storytelling visualization platform within Omeka.

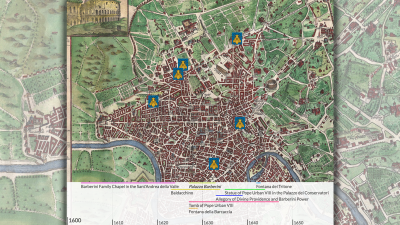

In Italian Baroque Art, students would learn about the creation and context of seventeenth-century painting, sculpture, architecture, and infrastructure, with a particular emphasis on urban settings and sociopolitical influences. Their final projects would combine this knowledge with primary research in Neatline to present analytical visualizations of such topics as the placement of papal tombs in Rome, the development of a family’s contemporary art collection, or the career of a female artist.

With the addition of Lazarus to the teaching team, students now had access to a resource that could help them both find historical sources and troubleshoot technical problems, a special advantage not always available in Wired! courses. Jacobs continued to lead the in-class workshops, but Lazarus became the first point of contact for questions about Omeka and Neatline while also assuming typical teaching assistant duties. This arrangement proved equally beneficial to Lazarus, whose assistantship was greatly enhanced by gaining teaching experience with both the historical material and the digital humanities tools.

Omeka and Neatline were introduced early in the course to give students time to learn the tool through practice projects and then to apply this knowledge to their final project research and presentation. For Lazarus, this meant more work early on in the course preparing for and then providing feedback on the practice projects. In preparation for the in-class workshops, held during two consecutive class meetings and followed by a practice project presentations, Lazarus created an example that helped students better understand Omeka and Neatline’s functions and possibilities.This activity also refreshed her knowledge of the tools and gave her an opportunity to review and provide feedback on some of the lab’s written tutorials on Omeka and Neatline.

During and after the in-class workshops, Lazarus answered questions and addressed technical issues. Following student presentations of their practice projects, she presented a list of best practices, drawing examples from student work, to encourage students as they advanced their use of Omeka and Neatline. By the time students began preparing their final projects, Lazarus had a firm knowledge of Omeka and Neatline and how to best adjust their use to fit both historical materials and students’ needs.

Lazarus worked with Dr. Lanzoni to identify possible topics for student projects that would benefit from spatiotemporal visualization based on her knowledge of both the course content and the tools’ affordances. She continued providing vital consultations and feedback through the remainder of the course, guiding students in the creation and continued improvement of their final Neatline exhibits.

This method of teaching and learning--mastering digital tools by creating an example project, providing one-on-one consultations, and giving detailed topical and technical feedback--proved invaluable for Amanda Lazarus’ academic development. While it required additional work before and during the first half of the semester, more than may be customary for art history courses, this work prepared her to better contribute as an instructor during the critical second half of the course. By having a firm understanding of Omeka and Neatline, Lazarus could assist students. By answering students’ questions, Lazarus continued to develop her technical skills and pedagogical understanding of the tools. Moreover, in adopting a teaching and learning approach, Lazarus reports immeasurable professional gains as both Dr. Kristin Huffman Lanzoni and Hannah Jacobs were generous mentors in their respective specialties throughout the semester.

When asked what advice she would give graduate teaching assistants for future such courses, Lazarus highlighted the importance of reserving time to work through tutorials as early as possible in the semester. She also emphasizes the need to experiment with the tools in order to think through possible ways students might push the boundaries of their projects. With regard to the overall experience, Lazarus reports that collaboration among the instructors was critical, as each member of the team both gained and contributed knowledge, forming a richer educational experience for all.

This teaching model was deemed a success, and the Wired! Lab, along with the Center for Instructional Technology and Digital Scholarship Services, is implementing similar structures to two other courses in Spring 2017. Student projects from ARTHIST 256 Italian Baroque Art are available for exploration at http://baroque.trinity.duke.edu, a website generously hosted and supported by Trinity Technology Services.